There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ treatment in mental health.

Some experience growth through new habits and the guiding support of counseling, while others heal through carefully prescribed medication or under the structured care of a hospital.

“There’s definitely a spectrum in terms of where our graduates are going,” said Ben Willis, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Counseling and Human Services. “That’s really what the program is geared for: to help students find their own way to become a counselor, because we need people with lots of different specialties and areas of expertise.”

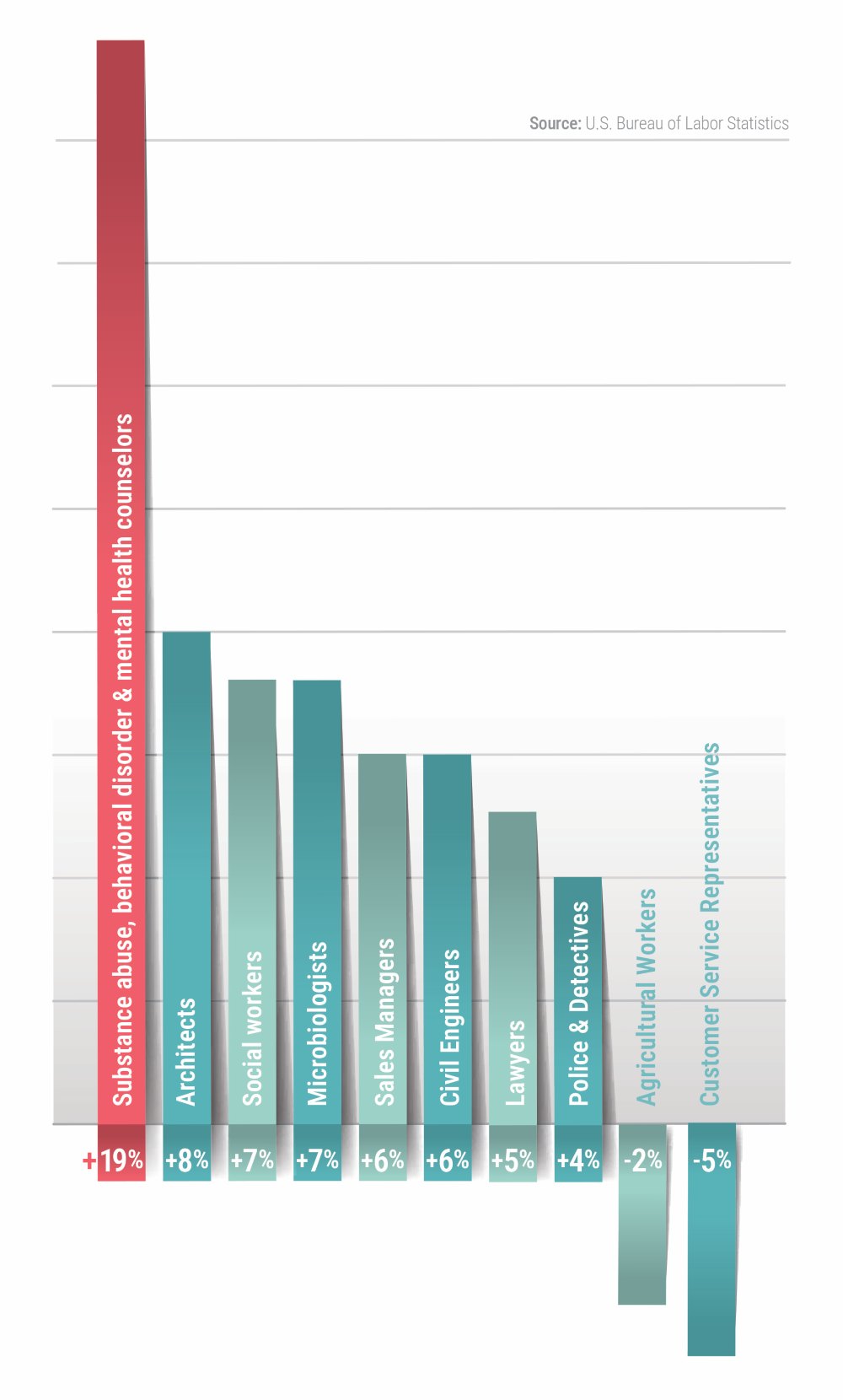

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 19% increase in employment of substance abuse, behavioral disorder and mental health counselors from 2023 to 2033. On average, occupations have a 4% growth rate. There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ treatment in mental health.

The expansion of specialized subfields and the growing number of clients have created an urgent calling — one that’s been answered by The University of Scranton.

In addition to an undergraduate counseling and human services major, the University’s Department of Counseling and Human Services has three graduate counseling programs: clinical mental health, clinical rehabilitation and school.

“All three of our graduate programs lead to being able to be a licensed professional counselor,” said Gerianne Barber ’84, G’88, director of the Counselor Training Center. “They have slightly different focuses, but a lot of the education is the same — including their practicum experience."

“I’ve been here for 20 years, so now I’m seeing some students who I worked with early in my career being leaders in the community and doing great things” — Rebecca Spirito Dalgin, Ph.D., chair of the Counseling and Human Services Department

The University has two in-house training centers — the David W. Hall Counselor Training Center inside McGurrin Hall and the newly reopened Leahy Counseling and Behavioral Health Clinic on Mulberry Street — where graduate students complete supervised, hands-on practicum work.

University of Scranton graduate students during the 2023-24 academic year acquired more than 1,500 hours of counseling at those facilities. Clients visiting the counselor training centers are often students struggling with academics, developmental adjustment concerns, relationships or any number of other personal/developmental issues.

“We’re trying to meet a mental health need on campus, as well as in the community, while also educating the next generation,” Barber said.

FACT: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 19% increase in employment of substance abuse, behavioral disorder and mental health counselors from 2023 to 2033.

That next generation includes students such as Brooke Martin ’26, a nursing major from Hunlock Creek, who decided as a sophomore she wanted to specialize in mental health care.

“The University of Scranton’s Jesuit values, especially cura personalis, show that caring for the whole person is important,” Martin said. “Mental health conditions

like depression or anxiety, when not addressed, can spiral into physical conditions that leave people isolated. But if these issues are addressed early, individuals have a better chance at an improved well-being and reintegration into daily life.”

Martin will continue her education at Scranton as a student in the new psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner (PMHNP) program. Students in the program, which is within the Department of Nursing, can pursue either a Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) or Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP). Classes began in the fall 2025 semester.

“Graduates from our program will be trained across the lifespan so they can work with children, older adults and everyone in between,” said Barbara Buxton, Ph.D., director of the psychiatric mental health nursing program.

“The University itself was very supportive of this program, recognizing the need for mental health practitioners not only in our area but statewide. There is a need everywhere for people with this kind of training.”

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) estimates that nationwide demand for Psychiatric Nurse Practitioners will rise 18% from 2016 to 2030.

Unlike counselors, psychiatric nurses require medical training because they can prescribe medications to individuals in need of psychiatric and medical care. They are licensed to diagnose and treat conditions that include both mental and physical symptoms, such as bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, sleep disturbances and substance withdrawal.

Dr. Buxton, who has been a faculty member since 2005, worked 20 years as a mental health nurse before entering academia. She reflected on how much the field has evolved.

“I can honestly say that nursing school was one of the most stressful times of my life,” Dr. Buxton said. “Did people think about the mental health of nurses then? That has changed significantly now.”

As of August 2024, the HRSA reported that 122 million Americans lived in areas with a shortage of mental health professionals.

Yet, heightened public awareness and a surge in educational programs — evidenced by what Scranton and others are doing — suggest that meaningful progress is underway.

“I’ve been here for 20 years, so now I’m seeing some students who I worked with early in my career being leaders in the community and doing great things,” said Rebecca Spirito Dalgin, Ph.D., chair of the Counseling and Human Services Department. “It’s exciting to see the impact, to see the ripple effect of the work that we do here on campus.”