While many of the students of Prof. Paul M. Jackowitz ‘77, P ’11, ’16, assistant professor of Computing Sciences at The University of Scranton, have heard him discuss the unintended consequences of new technologies in the years since he first joined the Scranton faculty in 1982, most of them likely don’t know that Jackowitz would never have embarked upon a career in computer science without the intended consequence of a scheduled meeting with his high school guidance counselor concerning his future after graduation.

“I sat down, and (she) said, ‘What do you want to do when you graduate?’” Jackowitz recalled. “Now, I’m 17 years old, and I haven’t the faintest idea. And, the guidance counselor said, ‘Well, you get good grades in math – do you like math?’ And I mumbled, ‘Yeah, I like math.’ And (she) said, ‘You don’t seem enthusiastic.’ And I said, ‘Well, it’s kind of all the same stuff.’ And she said, ‘Well, what about … computer science?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know what that is.’”

Programming Beginnings

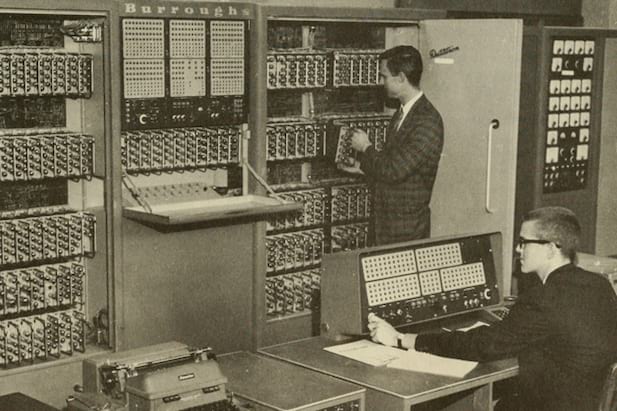

The South Scranton native began formally learning about computer science during the fall of 1973, three years after the University first listed “Computer Science” as an option in its course catalog. At the time, the University, which was the second American Jesuit university to offer a computer science major, had one lone, room-sized Xerox Sigma 6 computer located on the first floor of St. Thomas Hall for its students to use.

“It was behind a brick wall,” Jackowitz said. “You never saw it. There were a couple of holes in the wall. In the one hole, you put your punch card decks with your programs, and, in the other holes, you got a printout back, and that’s how we interacted with computers on campus in the early 1970s.”

"You didn’t go to an app store and browse for what you wanted."

Jackowitz soon applied for a work-study position as a computer programmer in the Computer Center, a non-academic department that managed and maintained the computer. In that capacity, he began developing software for the University.

“We were (writing) production software that the University was using,” Jackowitz said. “Generally, in those days, most software was developed in-house. You didn’t go to an app store and browse for what you wanted.

“It was a great learning experience. Personally, I grew in confidence knowing I was actually doing what I planned to do upon graduation.”

By the time he was a senior, the University’s computer system had evolved to the point where it could serve multiple users at multiple terminals, monitors, and keyboards in a process called “time sharing,” which eliminated the need for punch cards and printouts. While this innovation impressed the young Jackowitz, he found himself even more impressed by JoAnn Sopinski, a fellow Computer Science major at the University who would go on to become the future JoAnn Jackowitz ’79.

“I noticed her, she didn’t notice me, but I worked on that,” Paul joked.

After graduating in 1977, Jackowitz began working at the University as a faculty support programmer analyst, where he assisted faculty members interested in using computers in installing software intended for student use. Soon afterward, he moved on to Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute, where he began working on a master’s degree in computer science. And, it was during that time that an unintended consequence of his education pointed him in the direction of his future life’s work.

Disruption

“I started teaching here at Scranton in ’82,” he said. “I had no intention of doing that, to be honest with you. The plan that JoAnn and I had was that I’d go off to graduate school … and then get some high-paying job somewhere and take it from there.”

While working on a research project, however, Jackowitz had an epiphany: He could share his knowledge with others as a career.

“This may sound, I don’t know, maybe too presumptuous, but it just dawned on me, ‘Geez, I could do this just as well as anybody else,’” Jackowitz said. “I’m going to give this a try.”

Jackowitz returned to campus as a faculty member to find that the University’s computers had steadily evolved to include a Data General minicomputer, a device about the size of a small closet that required substantially less air conditioning and ventilation than the mainframe-sized units of the past. Not long after he began teaching, the personal computer revolution hit the University.

“(It) was really quite disruptive because the whole idea was that each individual would have their own computer,” he said. “They didn’t have to rely on (having access) to somebody else’s computer. This, of course, leads to the whole dawn of a new software industry, people writing software for that personal computer market.”

And, while Paul was teaching and JoAnn was working as a programmer analyst at InterMetro Industries, their family experienced three benevolently “disruptive” events of its own: the births of their children Andrew, Daniel ’10, G’13 and Lisa ’16, G’19.

“When you have a child, so much changes,” Jackowitz said. “One of the things you discover is that as a parent, you certainly are a teacher, so the way you’ve learned to sort of present things kind of spills over into your personal life and into your children.”

A New Day

Just as the world-at-large was becoming used to the new normal of the personal computer era, the enhanced connectivity of the internet came along to disrupt the industry yet again. From there, the content available on the internet exploded, leading to a number of advances that seem commonplace today but were truly revolutionary in their impact.

“Take … something like Wikipedia,” Jackowitz said. “You want to find out about something, and you type ‘Something Wikipedia,’ and it takes you right to the article. Our librarians here on campus will say, ‘Well, you know, that‘s not necessarily a very reliable source,’ but everyone generally agrees there is some merit there.”

"It’s the concepts that will serve you your whole career."

From there, Jackowitz said the economy created by the marketing of the internet and, later, the marketing of the smartphone, led directly to advancements in specialized areas of the field, including cybersecurity and social media. The possibilities for the future of the field, of course, remain limited only by the imaginations of future computing scientists.

“When you work with physical stuff, you’re limited by the physical realities of the natural world,” Jackowitz said. “When you work with computers, it’s abstract. You can imagine these virtual things.”

Recently, the Department of Computing Sciences celebrated the 50 th anniversary of the establishment of the degree program in Computer Science at the University with an alumni Zoom social, and Jackowitz said the department has planned additional celebrations throughout the coming year to commemorate the occasion.

“Fifty years of computing at Scranton is a milestone that we in the department are very much proud of,” he said. “I think (the Zoom social) was a success because people asked, ‘When is the next one?’”

And, although much has clearly changed since 1973, today’s students still study many of the same lessons Jackowitz learned during his student days.

“There are concepts, and there are details when you study computer science,” he said. “It’s the concepts that will serve you your whole career.

“The details (will) change … but when you walk out the door, you’ve got those concepts, and hopefully, you’ve learned how to continue to learn because you’re going to have to do it the rest of your career.”

Scranton Shorts: Celebrating 50 Years of Computing Sciences At Scranton With Assistant Professor of Computing Sciences Paul M. Jackowitz

On today’s episode, we sit down with Professor Paul M. Jackowitz '77, assistant professor of computing sciences at the University, to discuss the 50th anniversary of the computing sciences at Scranton, his student days and the lone, room-sized computer the University housed, his time on the faculty, and the evolution of the program from punch cards to pcs to smartphones and beyond.

Listen to the podcast episode, here.