NINE HOURS TO WAIT.

Nearly at the peak of Mount Everest, alone with his thoughts, Dan Akerman ’06, lay in his tent on Friday, May 13, waiting for his Sherpa to tell him it was time to attempt the night climb to the mountain’s peak — 29,029 feet.

They were camped in the “death zone,” appropriately named for the extremely harsh conditions and the impossibility of rescue so close to the top.

“In the ‘death zone’ every ounce of energy your body uses, it can’t recover,” said Akerman. “You’re slowly dying, essentially.”

Telling the story a month later, he was calm and spoke in a measured tone. He was — mostly — recovered, albeit with some frostbite. But, at the time, his mind was reeling, and his body was devouring energy.

“I was just turning things over in my mind: how I got started, and all the things I had to do to get to this day,” he said. “What happens if I don’t summit? How will that affect me in all aspects of my life? I was attempting to prove to myself that anything is possible. What if anything is not possible? How could I recover, mentally, from that?”

The Ascent

Five years ago, Akerman, a vice president of crisis management at Swiss Re, an insurance company in San Francisco, California, set his 2016 Everest plan into motion. He mapped out training schedules (he had already begun to train, climbing Mount Rainier in 2010, Aconcagua in 2012, Denali in 2014 and Manaslu in 2015) and calculated the cost of more than $50,000, which he then raised. All the while, he worked 40-50 hours a week and trained two hours a day, three or more in the months before the climb.

For Akerman, it took dedication.

“I always think of that quote, ‘Of those to whom much is given, much is expected.’ I think about that quote a lot,” he said. “I’ve been given so many opportunities,” many of which he attributes to his experiences at Scranton.

A decade earlier as a student, this international finance and business major wasn’t thinking about mountain climbing. What was “expected” of him, at that point, was making the Dean’s List.

“When he sets his mind to something,” said Lena Akerman, Dan’s mother, “he follows through.”

Dan Akerman was born in Sweden, moved to New York with his family as a toddler, then back to Sweden with his family at age 9. But before he moved back to his homeland, he promised an American friend (Michael Cassino ’06) that they would reunite at college in the United States. In 2002, they became roommates at Scranton.

Just like Everest, his mom noted, “he delivered 100 percent according to plan.” She recognized his determination, but admitted that his Everest climb made her, and the rest of the family, nervous. After all, avalanches in the last two years have killed 35 climbers and injured many others. And her son took on an extra challenge while there.

Through Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation, an organization that pairs explorers with scientists to conduct research, Akerman planned to collect three snow samples for researchers who are trying to prove that the Tibetan Plateau is melting at extremely high altitudes. To do so, he would have to make his way deep into crevasses in three different places along his Everest route and send the samples back to Denver.

The Peak

Akerman arrived in Kathmandu, Nepal, by way of his home in Sweden on March 30. He hiked alongside two Sherpas, who had a combined 25 Everest summits.

Because of the snow samples, Island Peak — the “warm-up mountain” and the least technically challenging part of the climb — proved difficult for Akerman. Around 19,600 feet, there was no crevasse safe enough to climb. So he had to dig. Into the ice. Seven feet down. It took five hours, but he managed to get the first sample and send it off. He easily got the next two samples.

Eventually, he and his team got to Everest Base Camp. Because they were already acclimated to the high altitude from their extra time on Island Peak, they decided to go straight to Camp III. Usually, climbers do rotations up the mountain to adjust their bodies to the altitude.

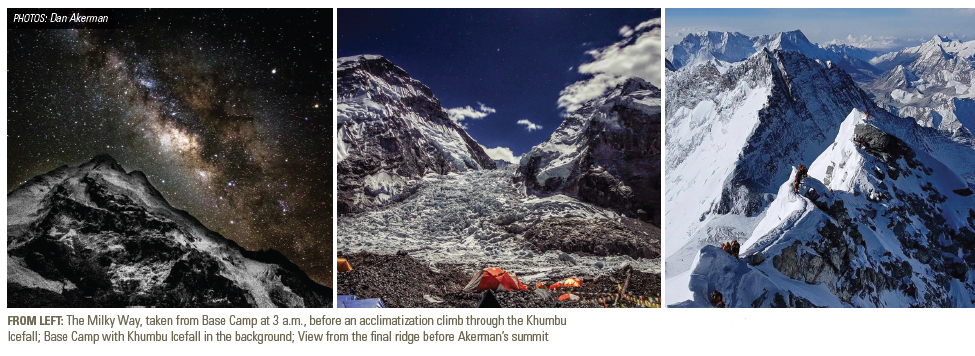

They made it to Khumbu Icefall, a craggy, treacherous expanse of ice. “The ice blocks are always teetering. They will collapse at some point, but hopefully not when you’re underneath them,” said Akerman. “There are some risks you can’t control.”

They arrived at Camp III, halfway up the Lhotse Face, on May 12. On Friday the 13th, they were at Camp IV. Wind prevented many groups from attempting to summit, yet Akerman and his team decided to make their ascent. Within an hour, he couldn’t feel his toes. But, as usual, he was committed to his goal.

“I was just so set on getting to the summit then … bad weather? It didn’t faze me,” he said, citing summit fever. “There was nothing stopping me.”

“Colors started building on the horizon at 4:30 a.m.,” he said.

At 5:47 a.m., Akerman reached Everest’s peak. Suddenly, he was scared.

“If I can’t get down on my own two feet, I’m not going to get down,” he recalled thinking. “I might freeze to death. I could potentially die today.”

After 34 minutes on the summit, Akerman and the Sherpas made their descent. No one else had gone up that day due to high winds. When they approached Camp IV, people emerged from their tents and pointed into the swirling snow. “We must have seemed like ghosts coming off the mountain,” he said.

Once they made their way down through Khumbu Icefall, he breathed a sigh of relief. Then, almost immediately, he set another goal. As he checked Everest off his list, he devised a plan to reach the highest peak on every continent, “the seven summits.”

For now, though, Akerman is readjusting to his normal routine as a businessperson in San Francisco, sitting at a desk with frostbite on his toes.