Mahon’s most treasured role was the chief of the Los Angeles Police in “L.A. Confidential.”

John Mahon was 12 years old, a devout Catholic, when he strode confidently up the stairs into a school dance in his hometown of Scranton. A moment in time that should have faded into distant memory — remembered only by the anxiety that might come from asking a girl to dance — became a major turning point in his life. He did not get the chance to ask anyone to dance that evening. Instead, as he arrived, a current of pain went through his body and he fell. He managed to exit the building and drag himself home. He was unconscious for the next several days. He had been stricken with polio and completely paralyzed, but he considers himself lucky, having left the hospital with only the loss of use of his left arm.

As Mahon ’60 tells it in his recently published memoir, titled A Life of Make Believe: From Paralysis to Hollywood, while he was the hospital he felt “helpless,” “alone” and “imprisoned” in his body. Despite years of fear and paralysis, he gradually gained back confidence (in addition to a cheeky sense of humor). He eventually became a stage, television and film actor (appearing in many movies, including “L.A. Confidential” and “Armageddon”). He also found a second calling along the way, as a mentor to actors with disabilities.

The Acting Bug

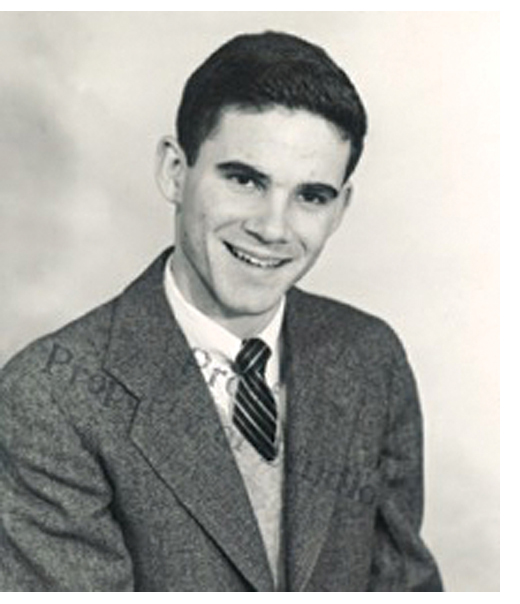

The acting bug first bit Mahon at age seven, when he had one line in a variety show at the local Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) post. The applause produced feelings of appreciation foreign to a boy who grew up in a “dysfunctional household.” The stage became a second home when he was a student at Scranton Central High School (yearbook photo at right).

He continued to act while at The University of Scranton, where he studied classical languages and literature. It was in his sophomore year that he met Jack Miller, later to be called Jason Miller ’61, H’73, actor and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright. Miller, who would become a lifelong friend, suggested that Mahon audition for plays at Marywood College (now University). Soon after, along with his classmate Chaz Bennett ’60, he joined the University Players at Scranton, where, he admits, his grades suffered because “all I wanted to do was act.”

In a performance alongside his fellow alumnus, Miller, while playing the Inquisitor in a production of Jean Anouilh’s “The Lark,” he realized that there was more to acting than awaiting cues and saying lines. The bishop of Scranton happened to be at that performance. Mahon remembers him coming backstage after the play and saying: “My son, I think you’re destined to preach the word of God from the stage.”

Such high praise from a bishop overwhelmed him.

His Callings

The day after graduating from Scranton, he was on a train to New York City, which he called “the capital of my imagination.” He took a job with a major corporation, supervising the production of two paper mills. After staying with the corporation for two years, he came to a decision to try to become a professional actor, even though he felt it was a “hare-brained, nutty thing to do,” given the fact that he only had the use of his right arm.

After acting in several off-Broadway plays that enjoyed brief runs, he found himself driving cabs, busing tables and temping. Still, when he made the decision to act, “I wasn’t going to quit, come hell or high water.”

Eventually, Mahon flew to Los Angeles to try his hand at television and film. He stayed for a year before returning to New York to play a bit part in “The Exorcist.“ While in New York, he directed Broderick Crawford in a production of Miller’s “That Championship Season.” He also directed “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” with Pernell Roberts (from “Bonanza”) playing the lead role. Mahon even received a “best director” award from the Council of Stock Theaters. Cary Grant presented the award.

Mahon returned to Los Angeles intending to stay for two weeks, but stayed for more than 40 years, acting in everything from “Austin Powers 2” to “The American President,” from “M*A*S*H” to “MacGyver.” Even with the loss of an arm, he was typecast in law enforcement and military roles.

“Everything I did in the land of illusion, I couldn’t do in life,” he said.

When Mahon was approached to teach a class to actors with physical disabilities, he said yes. And once he taught, he was hooked. He found that he was a natural at it and was thrilled to give back to a community with which he so strongly identified.

“Then I understood why I got polio,” said Mahon. “Honest to God, it was all serendipitous.”

To see clips from some of Mahon's movies click here.